This is a part Uncovering Japan This collection of stories highlights the lesser-known gems in Japan that should be on your itinerary. They include everything from vibrant street food to local craft, and traditional wellness. Read more here.

The tarmac is so rough that I can’t even walk on it. Fukuoka At the airport my umbrella is turned inside out and I’m wondering whether my flight even takes off. As soon as I board the plane, I buckle up nervously and we fly into a gloomy sky. But just 20 minutes into our 40-minute flight from Fukuoka to Fukue—the largest and most populated of Japan’s Gotō Islands, population 38,000—the skies clear. The small twin-propeller DHC-8 400 dips its wing to begin its descent. I catch the first glimpse of these fabled subtropical Japanese islands, also known as the Islands of Prayer. The moment is right, because I was praying uncharacteristically to the gods when we took off.

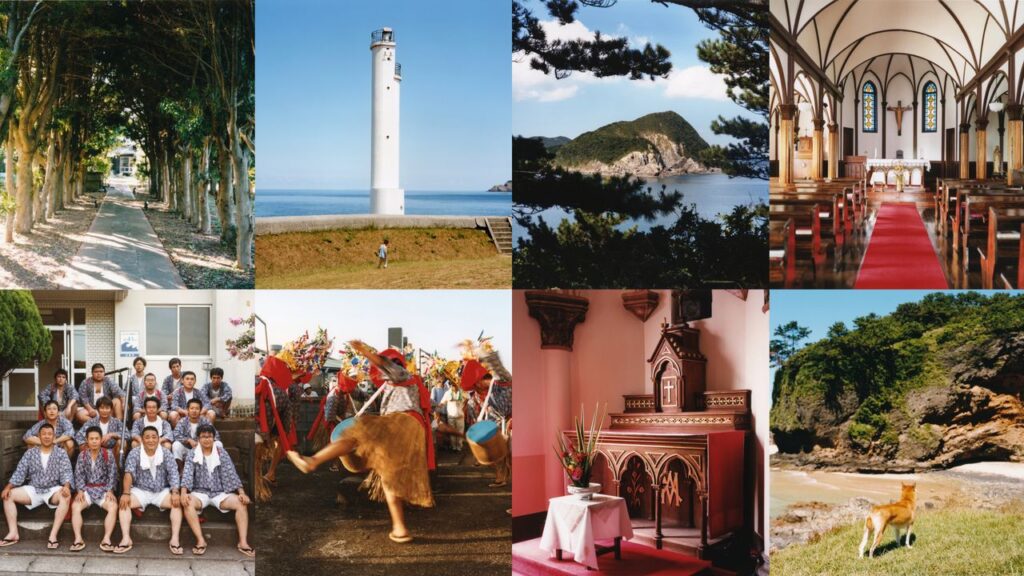

The choppy, shimmering Sea of Japan is dotted with green peaks. There are swaths covered in forests, palm trees, golden-sanded beaches, basalt coves, and sleepy port towns with wooden fishermen’s houses and bobbing boats. In recent years the Gotō Islands have drawn urban transplants from Osaka, Tokyo, Fukuoka and other cities are seeking a slower pace of living, more in tune with nature’s rhythms. The result has been new cafés, izakaya, galleries, and inns across the area. But the Gotō Islands are not just a picturesque destination for visitors seeking reinvention; they’ve served as a cultural bridge to cosmopolitan mainland Asia ever since they became a sanctuary from insular Edo-era Japan in the 1600s.

To really decipher the Gotō Islands requires understanding two things: their history and geography. The Goto Islands are located just 50 miles from Japan’s south-west coast. KyushuFukue Island is located in Nagasaki’s Nagasaki province and is home to the island’s largest city and port (just 146 mi west of Jeju Island, South Korea). You’re 200 miles closer. Shanghai than Tokyo, and it and the other four inhabited Gotō islands have their own volcanic, subtropical flavor that’s like nothing else in the Land of the Rising Sun.

During the Edo period (1614), Japan prohibited Christianity. Japanese and foreign believers who were persecuted sought refuge on the islands. Fukue now has 50 Christian churches. Many of them have been rediscovered over the years. UNESCO World Heritage status In 2018, But don’t think for a minute the islands are not Japanese; there are also numerous Shinto shrines, Buddhist temples, and plenty of izakaya and Japanese minka (farmhouses)—all things I love about Japan that have kept me coming back to the country for the last 15 years.

Long before the Edo era, the Gotō archipelago was an important stop for the maritime traffic of China, Korea, and Japan between the seventh and ninth centuries during China’s golden-age Tang dynasty. The Japanese political and cultural ambassadors to China, then a prosperous country, would make a stop at the island of Fukue on their way into Asia. And new ideas from Asia would first land here: Japan’s famous eighth-century-born priest Kukai (Kōbō Daishi) was one such passerby; he founded the Shingon school of Japanese Buddhism, which helped spread the religion to Japan. A statue of him can be found on Kashiwazaki Cape on the north shore, and in 806 CE he is said to have visited Myojoin Temple in Gotō City, the oldest wooden structure on the island and prized for its ceiling decorated with 121 paintings of flowers and birds.

Kukai was also only passing through. I spent three nights in Gotō, a decent amount of time to visit the main island of Fukue, though you could easily spend a week or more. For the first night I stayed in Fukue’s biggest city, which was renamed Gotō in 2004, after Fukue port merged with the towns of Kishiku, Miiraku, Naru, Tamanoura, and Tomie. The Goto Tsubaki hotel is located directly across the road from the port, where passengers are dropped off by the 30-minute jetfoil ferry from Nagasaki.

Ishida Castle is just a few minutes walk from my hotel. This castle was completed in 1863 and one of Japan’s last. Only its gate and moss-covered fortified walls remain, and the site now houses the Gotō Municipal High School, a cultural center, Gotō’s tourism office, and a public library, all located within the former castle’s walls. Next door is the former Lord Gotō Residence, a traditional house built in 1861 with tatami mats, fusuma sliding doors, a Japanese garden, and a pond shaped into the Chinese character for “heart” (心) designed by Zensho, a Kyoto monk.