You can also find out more about FFrom my rooftop terrace, I can see the Ourika River winding its way through the palmerias that line the southern edge. Marrakech. It’s difficult to imagine that I am only 20 miles away from the Djemaa al Fna square, and the noise of its souks.

“Salam alaikum,” says Abdelkarim Ait Ali, owner of Ourika Lodge (doubles from £53), as he loads my already groaning table with the generous breakfast offerings that are part of traditional Amazigh (Berber) hospitality. “There are many [hot air] “Balloons this morning!” “Balloons this morning!” he shouts, as he pours glasses of scented tea.

It was only recently that I noticed the specks of dust in the sky, now I can count over 20 as they drift eastwards, carried by the breeze at dawn. The realisation that even the skies are crowded makes it easier to picture the ruckus that reverberates through one of the world’s most vibrant cities each morning.

Marrakech is still my favorite city. I fell in love with it during my first assignment three decades ago. For the moment, however, I’m immensely grateful that I’d decided to base myself in Ourika valley, where the only sounds this morning are the sizzling of my Berber omelette and the braying of a mule from the mountain trail behind the house.

Abdelkarim led me into the mountains on a hike the day before. I was amazed that such pristine wilderness can be found so close to a metropolis of one million people. Abdelkarim, the son of a Blacksmith, now leads tours and expeditions in the High Atlas region and beyond. He shows me carob seeds with chocolate flavour and cypress seed pods harvested for what French colonists called le poivre des pauvres (the poor man’s pepper). He told me, “Mountain People place dried oleander on a fire in order to create antiseptic fumes.”

The sound of a wild pig tearing through the vegetation comes from the ravine. She emerged from the thicket and five striped piglets were hurrying to catch up. We are fortunately downwind, so she was unaware of our presence.

On the distant peaks of Toubkal, patches of white snow glitter. It has been four years since north Africa’s highest mountains had a proper snowfall, and the ski-season at nearby Oukaïmeden has been almost nonexistent once again this year.

Experts believe that African Wolves are making a return in the High Atlas valleys. The last wild Atlas Lion was shot in 1942 near these high peaks. It’s easy for us to imagine the wolves finding plenty of food if they returned. Abdelkarim explained that the boar populations are almost at infestation levels as their meat has become popular. The haram (forbidden by Muslims). They are worried that the drought will bring them more into contact with villagers as hungry pigs continue to raid fields and homes on a daily basis.

The farmers have had a tough time, he says. Spring meltwater rather than rainfall is the primary life force for the Ourika valley’s fruit orchards, olive groves and saffron gardens.

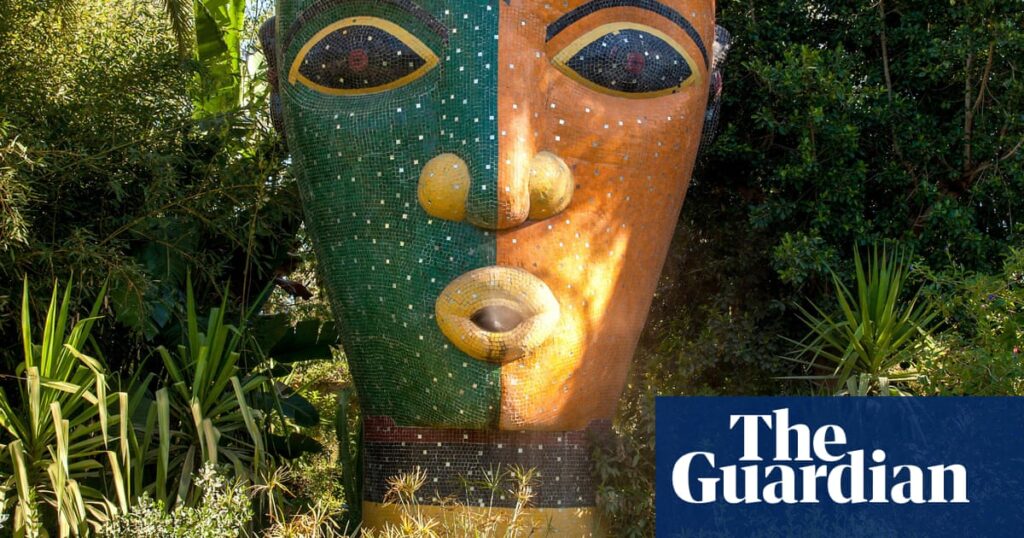

Marrakech has many photogenic gardens, but the most famous is its ‘Garden of Eden’. Jardin MajorelleYves Saint Laurent bought the company in 1980 with his partner. In recent years though, more and more visitors are choosing to escape the city in order to spend some time in Anima Garden, established by Austrian artist André Heller on what had been arid wasteland just north of Ourika. Anima is a peaceful, labyrinthine garden with mystical sculptures and tropical plants. I also love the low-key charm of its lower-key gardens. Jardin du Safran nearby.

Here I discover how the valuable “red-gold” of Morocco, saffron is harvested. Morocco’s mint tea, which is delicious and refreshing, is well-known, but I prefer the saffron scented tea that I enjoy on a terrace at the Jardin du Safran in an orchard with persimmons kumquats, and clementines. Even among the mind-boggling assortment of flavours – thyme tea, sage tea, lavender tea, absinthe, even artemisia (AKA wormwood) tea – that are popular among the Amazigh, this is a highlight.

After Newsletter Promotion

Rural markets rotate around villages on a daily rotation, providing a fascinating contrast with the spice, carpet, and basketry souks found in the cities. We fuel our explorations of the Aghmat Friday market with sweet Ouarzazate Dates and a sugarcane-juice tangy from crushed ginger.

The ongoing excavations at the Aghmat archaeological site show that the now humble village, which was once the capital of the region for over 700 years before the city moved to its current location in Marrakech during the 11th century. Before archaeologists started restoring Aghmat in 2005, potters occupied the brick domes of Aghmat’s majestic hammam.

The restoration project was largely unaffected when the 6.8-magnitude earthquake struck on 8th September 2023. It killed almost 3,000 people, and destroyed or damaged an estimated 60,000 homes. Half of the homes in the pottery village Tafza were destroyed. It is located near the mouth Ourika Gorge, 40 miles away from the epicenter.

Khalid ben Youssef says to me, “It is strange how fate works,” when I arrive at a pottery class at his workshop Tafza. “When we were clearing up the rubble, we discovered a huge stone slab engraved in Hebrew. When I eventually got it translated I learned that it bore the date 1575 and was etched with the name of my ben Youssef family!”

Tafza is still struggling to accept the destruction. But the years of drought were kind to the ceramic industry. There’s been a good amount of drying, so the roofs and courtyards are always piled high with terracotta tagines, bowls, and pots. Khalid’s guidance is more than enough to teach me how to make a beautiful piece of pottery, even though I am a novice. Tangia Pot, a traditional slow-roasted meat dish.

Weekends see the Ourika’s upper banks adorned with colorful parasols, floor cushions and tangia pots. Chefs in scores of riverside cafés prepare tagine stews with beef, chicken, rabbit, vegetables and tangia.

Ourika Valley’s top tourist attraction is the series of seven beautiful falls in Setti Fatma Village. On the way up the valley, sightseers often stop to have their photos taken mounted on camels. Most visitors cross the river immediately after taking a selfie of cascade number 1.

But Abdelkarim guides me onwards up a narrow track – little more than a goat trail – which leads through a jaw-dropping chasm to the second, third and fourth cascades. After a half-hour, we arrive at the fifth cascade. A picture-perfect, natural plunge pool is the perfect picnic spot. It’s a world apart from the noisy restaurants along the river.

Abdelkarim says, “Few people, not even Marrakchis themselves, seem to know how much Ourika Valley has to offer.” We stare at the snow-capped mountains, also known as the Roof of Africa, while we gaze past the waterfall. It is amazing that our valley can be Marrakech’s best kept secret, despite being so close.